Philip J. Miller and Andres Bustillo

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, the need for nasal dorsal augmentation has increased. This is due in part to today’s enhanced nasal aesthetic evaluation, which focuses on harmony rather than on reductive ideals. The augmentation of the nasal dorsum can allow the rhinoplasty surgeon to improve nasal aesthetics to achieve a balanced appearance. Despite the plethora of available augmentation materials, there is not a perfect autologous graft or synthetic implant that is free of potential complications or consequences. This chapter addresses the ramifications of dorsal augmentation, including the material used and how to manage complications.

Anatomy

The nasal dorsum comprises the nasal bones and the middle cartilaginous vault. The bony and cartilaginous vaults are not simply joined at a seam; they are overlapping. Thus, after reduction of the bony hump by rasping, the cartilaginous vault is uncapped.

The cartilaginous vault is a single anatomic entity. It becomes a septum and two upper lateral cartilages after dorsal reduction. Resuspension of the upper lateral cartilages or placement of spreader grafts is aimed at recreating the normal anatomy. The shape of the cartilaginous vault changes from a T shape under the nasal bones to a Y shape at the rhinion and on to an I shape at the septal angle.

The soft tissue envelope varies along the length of the dorsum. It is thickest at the radix, in part caused by the procerus muscle. It is thinnest at the rhinion. The supratip area then becomes thick again, masking the downward sloping cartilaginous dorsum. These characteristics are not only important for dorsal reduction but also for augmentation. In much the same manner as the rhinon should be left as the highest part of the dorsum during reduction, the dorsal graft should have a gentle convex curve in the area that will correspond to the rhinion. This will allow for a straight dorsum.

Surgical Treatment

Augmentation Materials

The authors prefer cartilage for dorsal augmentation. The degree of augmentation determines the source of cartilage used. For small-to-moderate augmentation, septal cartilage is used. It is readily available in most rhinoplasties. In revision rhinoplasty, where the septal cartilage may have been harvested previously, auricular cartilage may be used. If the auricular cartilage has been exhausted, then a frank conversation with the patient must be performed. In this situation, the factors at hand include the amount of augmentation needed and the need for structural support.

In the absence of septal or auricular cartilage, when the revision rhinoplasty requires a small to moderate augmentation, Gore-Tex (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ) can be used. It is available in either layered sheets or in a solid block that is carved to shape. Advantages to Gore-Tex include the following: availability, the avoidance of an external thoracic scar, lack of resorption or warping, and its ability for tissue ingrowth. The latter will allow for the fixation of the implant. The main disadvantage is the risk of infection or extrusion, which is approximately 3%. Conrad and Gillman evaluated the use of expanded poly-tetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) implants in 189 patients undergoing rhinoplasty. Follow-up intervals varied from 3 months to 6 years (average, 17.5 months) with five cases (2.6%) of implant removal secondary to infection. Two implants were removed because of chronic inflammation and soft tissue reaction. No cases of implant extrusion, migration, or resorption were reported.

When a significant amount of dorsal augmentation is needed, the authors favor autologous rib grafts. Although the risk of infection with an autologous rib is significantly lower than with alloplasts, it is still a possibility and must be discussed. These infections do respond to conservative treatment, differentiating them from those involving alloplasts. Autologous rib may warp if not carved from the center. Carving should be performed in a symmetric fashion using the central core of the rib (as opposed to the peripheral area) to minimize warping. Allowing the rib to soak in saline in regular intervals during the carving stage will allow it to warp and thus the carving may be tailored. Some authors advocate using a K-wire through the center of the graft to avoid warping.

The rib is carved in a canoe-like shape and placed in a tight subperiosteal pocket above the nasal bones. The graft should be carved so that its lateral sidewalls align properly with the nasal sidewalls to allow for smooth dorsal aesthetic lines. The dorsum should be smoothed to allow for a proper base for the graft. Occasionally, a suture may be placed to secure the graft to the inferior dorsum just slightly above the anterior septal angle.

The authors strongly recommend autologous rib where structural support is needed. These cases often require the reconstitution of the L-shaped strut with costal cartilage. The dorsal segment is placed in a subperiosteal pocket above the nasal bones and locked in a tongue-in-groove fashion to the columellar strut, also made from costal cartilage.

Other materials used for dorsal augmentation include soft tissue fillers such as nasal or postauricular subcutaneous musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). These materials are autologous and have all of the advantages associated with such. Several authors have published favorable results with their use. The use of acellular dermis has decreased in the last few years, owing to less-than-favorable long-term results.

Irradiated rib has been described for dorsal augmentation. Proponents site avoidance of a second surgical site and the low incidence of complications compared with the use of alloplasts. There are mixed reports regarding the rate of resorption of irradiated rib. Murakami et al used irradiated rib cartilage to reconstruct 18 saddle-nose deformities. With a follow-up of 1 to 6 years (mean, 2.8 years), no cases of infection, extrusion, or noticeable resorption were noted. One (6%) graft had to be removed secondary to warping, and two (11%) displaced caudal struts had to be repositioned under local anesthesia. This may be a reasonable alternative in older patients who may have calcified ribs and need structural support.

Silastic (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) has a long history in Asia, where it is the most commonly used material for dorsal augmentation. Because a capsule forms around the implant, it fails to incorporate into the nasal tissues and may remain mobile. The literature is fraught with reports of Silastic extrusion and consequent skin loss and scarring. The authors do not have experience with the use of Silastic for dorsal augmentation, except for the occasional need to remove them.

Porous polyethylene has been used with success in various implants used throughout in the head and neck. However, its use in the nasal dorsum should be carefully contemplated. Its use as a cartilaginous substitute for structure is acceptable, provided there is sufficient soft tissue to cover all areas of the implant. The authors do not advocate its use in the nasal dorsum.

The future of implants for revision rhinoplasty may one day lie in tissue-engineered cartilage. It may possible to harvest a small sample of cartilage and generate sufficient cartilage for the procedure.

Surgical Techniques for Specific Complications of Dorsal Augmentation

Excessive Dorsal Augmentation

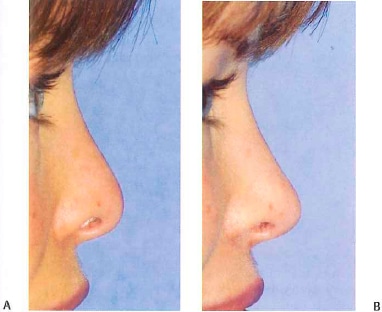

When the dorsum has been excessively augmented, the solution lies in conservative reduction. However, one should clearly identify that the problem is an overaug-mented dorsum rather than a nasal tip that lacks projection. The surgeon must make all efforts to identify the material used for augmentation. This will allow proper preoperative planning and patient counseling (Fig. 10-1).

Where small- to medium-sized cartilage grafts were used, simple reduction can be accomplished with a shave via an endonasal technique. This procedure preserves the nasal structure and avoids elevating the entire skin-soft tissue envelope.

In some cases, the dorsal profile appears to have an appropriate augmentation, but on frontal view, the dorsum appears extremely wide and unnaturally straight. This is often the case when a costal graft was used. The grafts in these cases have not been rounded sufficiently on their lateral edges. The effect is a steep drop-off from the nasal dorsum to the lateral sidewall. This is a tell-tale sign of augmentation rhinoplasty and should be avoided. Patients frequently seek revision surgery for this deformity. The authors often shave the lateral aspect of the graft via an endonasal approach. Occasionally, an external approach is performed if the revision requires additional work.

Where an alloplastic implant was used, the approach should reflect the specific material. If Gore-Tex was used, the approach depends on whether sheets or a block was used. Sheets may be removed and replaced with a lower number of layered virgin sheets. Blocks should be removed and either replaced with a newly carved block, or layered sheets maybe used instead. Where Silastic or porous polyethylene were used, Gore-Tex maybe substituted for the original implant. The option of autologous cartilage, if available, should be offered to the patient.

Figure 10-1 (A) Preoperative close-up photograph of patient who underwent previous augmentation rhinoplasty. Notice how the implant effaces nasion and pushes the nasal root too far cephalically. This situation resulted from placement of an implant that was too large. (B) Postoperative photograph of patient. Patient’s previous implant was removed and replaced with one B that allows for a more natural nasion placement and contour.

Insufficient Dorsal Augmentation

Patients who have undergone rhinoplasty with dorsal augmentation will occasionally require a second procedure to increase augmentation. Although graft resorption may occur, most are cases where insufficient augmentation was achieved primarily. Patients who were merely augmented when they necessitated structural support will experience collapse of the dorsal augmentation and ultimately present for revision rhinoplasty.

The approach used to further augment the dorsum depends on the material used in the previous surgery. The concerns that arise in these cases are the following: the amount of augmentation needed, the material used in the primary surgery, the availability of cartilage (septal or auricular), and whether structural support is needed. Where structural support is required, costal cartilage should be used.

Where structural support is not required, then the degree of augmentation and the material previously used are taken into account. If minimal to moderate augmentation is required, then SMAS, cartilage (septal or auricular), or Gore-Tex sheeting may be used. These sources can all be added above the previously grafted cartilage. However,

where silicone or porous polyethylene was used, the authors prefer to remove the implant and consider another material, such as cartilage or Gore-Tex. Where a significant amount of augmentation is required, our first choice is always cartilage. If cartilage is not available or the patient is not willing to go through a rib harvest, then Gore-Tex is used.

Warping

Warping often can occur when costal cartilage is not carved appropriately. However, even when meticulous techniques are used, there is a probability of cartilage warping. The treatment depends on the degree of warping. In most cases, the graft can be removed, reshaped, and then placed back in its pocket. AlloDerm (LifeCell, Branchburg, NJ) or temporal fascia can then be placed over the graft to fill in any small deficiencies that may exist. This technique also accounts for the small reduction in volume of the graft that may have occurred during the reshaping.

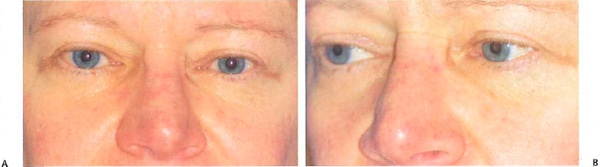

Warping also may occur secondary to the contractile forces of the fibrous capsule that forms around autogenous cartilage implants (Fig. 10-2). Treatment is removal of cartilage and surrounding fibrotic capsule with judicious reimplantation.

Figure 10-2 (A,B) Cartilaginous nasion graft. This patient underwent nasion effacement with morselizecl cartilage. Despite adequate cartilage softening, she formed a thick fibrous capsule around the graft, causing it to resume a more flat appearance. The edges of the graft became visible near the medial canthi and had to be removed.

Malpositioning

One of the most common complications seen in dorsal augmentation is graft visibility. This may be caused by a variety of factors. Thin skin, improper placement or carving of the graft, or a shifting of the graft all may contribute to graft visibility. Management of these complications is aimed at improving the aesthetics while minimizing surgical trauma. A minimalist approach may be all that is needed. When cartilage grafts were used in the primary surgery, the surgeon oftentimes can perform the revision under local anesthesia without the need to undermine the dorsal skin envelope. The first and most important step involves marking the defect area with a marking pen. This is done before any local anesthesia is infiltrated. The amount of local anesthesia is limited to 1 mL in most instances. When the defect involves an area that protrudes, it can be shaved. Using an 18-gauge needle, the skin over the area of concern is entered, and the edges are rasped with the needle. Small defects respond extremely well to this technique.

If the defect involves an area deficient in volume, several excellent soft tissue fillers may be used. Nasal or postauricular SMAS or deep temporal fascia may be used to camouflage a small graft irregularity in patients with thin skin. Most often this can be accomplished using local and topical anesthesia. It cannot be overemphasized that the exact markings should be made before any infiltration. We the use a limited amount of local anesthesia (usually 2 mL). An intercartilaginous incision is made, and a limited dissection is performed to maintain a small pocket. The graft then may be inserted into the tight pocket. We have not found a need to place retaining sutures when using this technique.

For larger defects, we use the endonasal approach with limited dissection of the soft tissue envelope. A number 11 blade is used on a long handle to shave the offending area. It is often the edge of the graft that needs to be softened in these situations. The graft may be removed if it is entirely visible. It can then be crushed and shaped appropriately outside and replaced. This approached also can be used for grafts that may have shifted.

Infections

Infections in patients with cartilage grafts are rare. These may occur by two distinct routes: direct inoculation (e.g., placement of an implant through a contaminated area) and hematogenously. When they occur, they must be managed aggressively to prevent graft resorption. Treatment is begun with systemic antibiotic therapy, topical antibiotic treatment with Bactroban (GlaxoSmithKline, Pic., Brentford, Middlesex, United Kingdom), and cultures are obtained. If the infection progresses to a frank abscess, an incision and drainage is performed. We have found irrigation with an antibiotic solution containing gentamycin using 20-gauge needles into the site to be extremely beneficial.

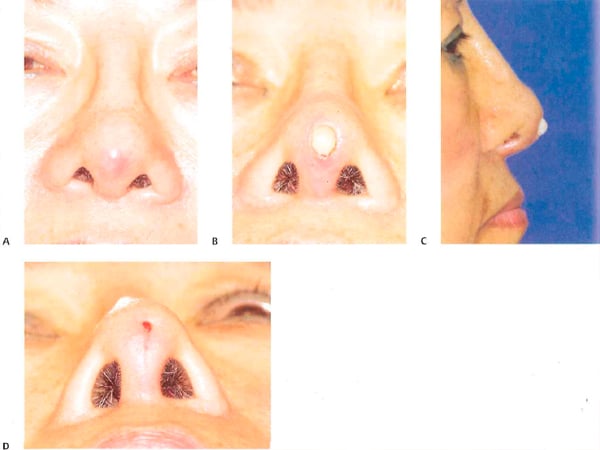

When infections arise in alloplastic nasal implants, the solution is expeditious removal. The risk of an infection progressing to and with involvement and necrosis of the soft tissue envelope is not worth any attempt at salvaging the implant. Reconstructive efforts may then be planned once the infection has resolved (Fig. 10-3).

Figure 10-3 (A-C) Erythema over the left dorsum indicative on an infected Gore-Tex graft. The graft was removed under local anesthesia, and the wound was irrigated. (D-F) These photographs show the patient 3 months later without further reconstruction.

Extrusions

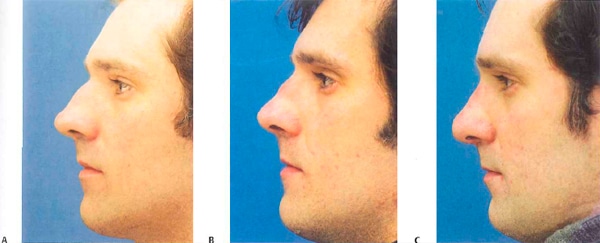

Extrusions of alloplastic implants are one of the most feared complications by rhinoplasty surgeons. Occasionally, the small implant may extrude through the skin-soft tissue envelope without consequence. This may occur when there is an absence of infection. Most often, however, there is a preceding infection that either develops rapidly or is inappropriately managed. Severe skin and soft tissue loss occurs, which will lead to unsightly scarring and skin contracture. Clark and Cook reported a series of 18 patients who underwent successfully reconstruction immediately. All patients suffered from alloplastic nasal implant extrusion and were treated with placement of irradiated costal cartilage12 (Figs. 10-4,10-5).

Figure 10-4 (A) Tip erythema is noted from an extruding dorsal/tip (Dow Corning, Midland, Ml) graft placed decades earlier. The patient ignored these symptoms, and several months later presented with the implant extruded (B,C). The implant was removed under local anesthesia, and the wound was left to granulate. (D) This photograph shows the patient 1 week after implant removal, with near complete closure of wound.

Figure 10-5 (A) Preoperative photograph revealing large nasal dorsal hump. Dorsum reduced and AlloDerm (LifeCell, Branchburg, NJ) placed to treat thin dorsal skin. The immediate postoperative period revealed a straight dorsum. (B) Four months after placement of AlloDerm on the dorsum. AlloDerm appears to have consolidated and condensed, resulting in nasal deformity. (C) After removal of AlloDerm.

Summary

The evolution of rhinoplasty has progressed to a more sophisticated aesthetic ideal. In the quest for the ideal dorsum, the surgeon often must provide dorsal augmentation to achieve a balance and elegant appearance to the nose. The risks, benefits, and complications of each option for dorsal augumentation should be conveyed to the patient and considered by the surgeon in selecting the ideal solution for dorsal refinement.