My Reception in Hanoi

Medical Volunteer Guide | Questions & Answers | Healing in Vietnam | Patients

Our trip from Miami to Hanoi began on a Friday morning on a flight to Chicago. Luckily, my wife and I had been able to upgrade our flight to business class with the miles we had accumulated over the past few years. The business class fare for this trip is extremely expensive and really only for executives and CEOs. Having made this long trip in coach several times and having to begin operating a few hours after arriving, I knew this trip was already starting off well!

An hour after landing in Chicago, we were on our way through the longest leg of the trip: Chicago to Tokyo. Interestingly, this part of the trip flew by. What a difference it makes flying like a CEO!

Thirteen hours later, we arrived in Tokyo where we enjoyed some authentic sushi for a late lunch. And soon we were off to Hanoi for the last leg of the trip. I remembered from the last few years, that this six-hour flight was the worst part of the journey. And it was no different this time again. We arrived in Hanoi at midnight and after waiting in a long line at immigration, we were allowed into Vietnam.

Two young residents from the National ENT Hospital were eagerly awaiting our arrival at the exit of the airport. After a 45-minute drive into Hanoi, they dropped us off in the small hotel where the rest of the team was staying. My wife and I were starving and because the small café in the hotel was closed, we went for a late-night walk through Hanoi. We came upon a beautiful hotel not far from ours and wandered in. We asked about having a late-night snack and were ushered into a quaint small restaurant in the back. We had a lovely light dinner and made it back to our room soon afterwards.

We woke up early the following morning with some difficulty and plenty of jetlag. If I were asked, what is the most difficult thing I experience in these trips to Vietnam, I would say the jetlag both there and once I return home. It must be that my internal clock is really slow, because it takes me weeks to acclimate to a new timezone. In Vietnam it is very difficult for me to sleep more than a few hours a night, and when I return to the hotel I’m usually out by 7 or 8 p.m.

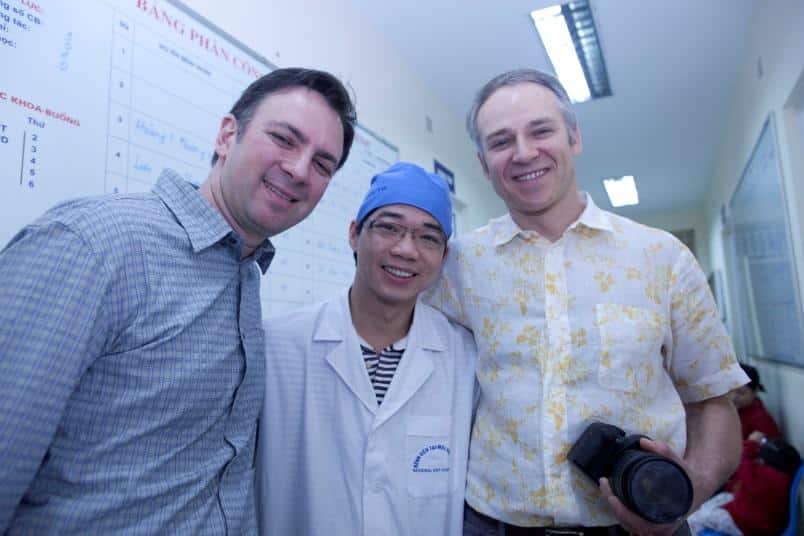

That morning the entire team had breakfast together in the hotel. It was nice seeing my fellow colleagues, Drs. Frank Fechner, Mike Nayak, Benjamin Solsky, and Henry Milczuk again. Frank and Mike are both facial plastic surgeons. I have known Frank for nearly 12 years. We both completed our fellowship in the same program. Benjamin is a mohs surgeon from Boston with great facial reconstructive skills. Henry is a pediatric otolaryngologist who is an amazing surgeon. On this trip, we had agreed we would all bring our wives. We were picked up by a van sent by the hospital and our wives went sightseeing around Hanoi.

It was Sunday morning, and once we arrived at the National ENT Hospital, we were taken to the ward to see the patients we would be operating on. We quickly met with some of the residents and professors and exchanged stories. We were all excited to find out the conditions of our patients from the previous year. We then began to see the patients we would be operating on this year. The professors and residents had previously seen all of these patients. They selected patients they believed needed the advanced, specialized care they were unable to provide. This is a very important part of the process. The self-selection allows them to pick and choose patients with surgical dilemmas that they cannot or cannot easily perform. By doing this, they are also choosing difficult surgical cases they wish to learn from.

Dr. Bustillo uses google glass to take you through a hospital ward in Vietnam.

We then discussed the surgical plans for the patients. All in all we saw approximately 25 patients requiring a wide range of facial reconstructive surgery, ranging from facial tumors, scars, cleft palates, to severe nasal injuries.

Ahn, one of the girls who had been operated on the year prior for a large congenital dysplastic nevus, was back for her second procedure. Because it surrounded the entire eye, the removal had to be staged, so as to not cause deformation of her lower eyelid. Removing too much in one surgery can pull the lower eyelid down, causing enormous harm to the function of her eye not to mention an unaesthetic result. Normally back in the states, this would have been done about six months apart. Approximately 60 percent had been removed in her first surgery and we planned to remove most of the remaining tumor this time.

I also had the heartwarming opportunity to see a patient I had operated on several years ago. I say heartwarming, because, unfortunately we don’t always get to see our patients again. This was a sad story of jealousy, where the boyfriend of a girl literally sliced off the entire nose of a teenager when he saw him talking to his girlfriend. We reconstructed his nose by harvesting a rib to rebuild the bridge and a forehead flap to provide skin to cover the new nasal skeleton.

That afternoon, after finishing at the Hospital we reunited with our wives and walked around Hanoi for a while. Hanoi has a special and pleasant character. The people are very nice and friendly. Walking through the city is a particular experience. The street-side restaurants are on the sidewalks, but the tables are about six inches off the ground with very low chairs. The cooking is done right on the sidewalks, whether they are grilling meats or boiling large pots of the local Pho, a delicious, light noodle soup with vegetables and meat. It’s a very busy city with thousands upon thousands of mopeds. Unfortunately, Hanoi has succumbed to heavy urban pollution like many of its Asian neighboring countries, as consequence of its industrialization.

On Monday morning we arrived at the hospital early. We walked through the familiar hallways and saw some of the families of the patients we were going to operate on. By the look on their faces, they seemed to be happy and excited. It was also nice to see some of the familiar faces of the ancillary staff that work in the operating rooms. We then met with the residents and professors and divided the surgeries amongst ourselves. Generally, if one of us has a particular forte, that person will take that case. For example, as I am fairly proficient in nasal reconstruction with rib grafts, I chose to operate on Coung, a gentleman who had suffered a bad motorcycle accident. He was not wearing a helmet, and landed face first onto the sidewalk. The bridge of his nose was crushed, obliterating his airway and essentially making him a mouth breather. Aesthetically, his nose was completely flat and he was extremely embarrassed to appear in public places.

I worked this case with Dr. Nayak and had the assistance of two residents. As an aside, after being in private practice for 10 years, it’s an extraordinary experience to be able to operate with residents and teach them as we go along. It brings back memories of being a chief resident in residence. In addition to the two residents who were scrubbed in the case, we had at all times at least 10 residents and several professors viewing the surgery from behind us. It truly is an amazing educational experience for the physicians in the hospital. Which inspires some thought and criticism regarding physician education in the United States.

The training in the United States is fairly rigid. Residents are taught in a highly structured fashion, both in the operating room and didactically. I get the sense that residents are more independent here. There doesn’t seem to be as much supervision and didactic teaching as in the United States. For example, I never saw a textbook lying around anywhere. Of course, it’s difficult and not fair to critically judge this, after spending only a week at a time there.

Many of the operating rooms in the hospital were set up with video cameras, so that even the residents who stood somewhat far from the operating-room bed could get an up-close view of the surgery. The cameras were attached to the operating room lights and fed to a video monitor on the same room. The operating rooms in Vietnam are somewhat different than in the United States. Although well stocked with recent technology, they lack the high technology seen in today’s hospitals in the United States. Nevertheless, I would describe them as adequate for our intentions. One notable difference from U.S. procedural norms is the idea of a dual operating room. In some rooms, two surgeries take place within the same room. I certainly don’t think the credentialing agencies in the United States would approve that.

Mike and I completed the four-hour surgery and met the rest of our crew in a small meeting room, where the ancillary staff brought us home cooked Pho and local fruit. We had lunch with the residents and discussed the day’s surgeries. This was always a nice time to review what we had done with them, hoping to teach basic and advanced techniques to them. That afternoon, we then met with the professors in a beautiful conference room in the new wing of the hospital.

The National ENT Hospital has just completed one of a series of three large expansions. Unfortunately, the new operating rooms were not ready for use, but we were promised they would be ready for the mission next year. The new wing that was completed looks absolutely extraordinary and seemed to have all the latest technology. We had a meeting with the Hospital’s director, Dr. Quang, who is always very nice and welcoming. He is largely responsible for our presence there. It is definitely not commonplace to have physicians come from the United States to Vietnam to operate and teach physicians. Dr. Quang is a bright and progressive-thinking physician who appreciates our expertise and contributions.

That afternoon, after all of our surgeries were completed, we met the residents and professors in their auditorium. We had all come with prepared lectures on important topics in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. One of the problems that strongly hinders our ability to teach the physicians there is the language barrier. Most of the professors understand and can get by with some speech. However, it can be very difficult to communicate with many of the residents.

I presented a one-hour talk on nasal reconstruction of the nose. The talk was simultaneously translated by one of the professors so that the residents would be able to understand it. Although the talk was centered on the reconstruction of nasal defects after mohs surgery for skin cancer, I took the opportunity to adapt it to their common, every-day problems. Because there are so many mopeds and so few of the riders wear helmets, there is an abundance of nasal trauma. I explained to them that the traumatic defects they so often encountered could be repaired in the same way that cancer defects of the nose are repaired.

That afternoon, we returned to the hotel to refresh and meet with our wives. Two of the professors had offered to take us out to dinner that night and we happily joined them. We were taken to a restaurant a few minutes away from the hotel. As we walked in, there were large aquariums lining the hallways with fish, eels, and turtles. We sat down, and as if everything had been pre-ordered, they began bringing food to our tables. At first glimpse, everything looked very appetizing. However, my wife and I soon found out they were serving us fried turtle and chicken heads. We gladly ate our servings of French fries and wine.

The rest of the days were spent in a similar fashion. We operated during the day and in the late afternoons lectured. At night, we were often invited by either a resident or a professor to their home to have dinner. They were all very welcoming and delighted to have us join their family for dinner.

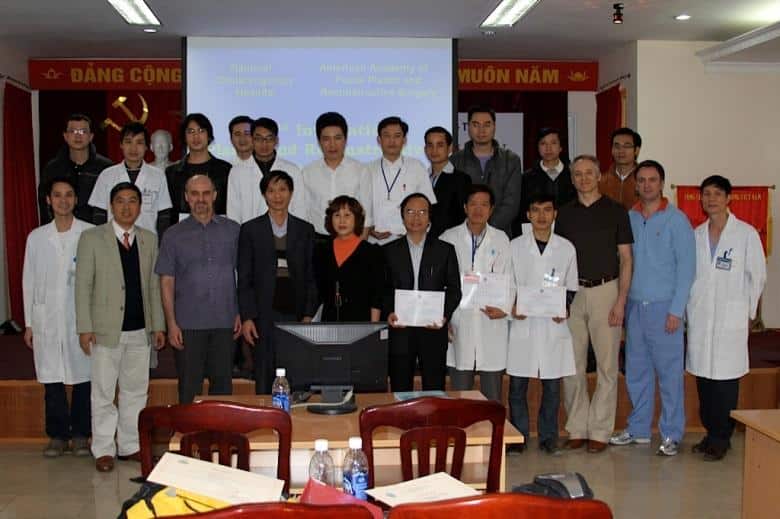

The last day, after we finished operating, the entire department held a ceremony for us. We were each given a plaque thanking us for our participation . The hospital also gave us a gift, as a token of their appreciation for our efforts to both help out with difficult surgical cases and for our help in the education of their resident physicians.

My wife and I left the next day early in the morning. Our return was routed through Shanghai and we had previously asked our airline to change our flight so that we could stay the maximum of two days without changing our fair. We were able to see most of the attractions and savor several local restaurants. Our return home was uneventful and we are already looking forward to next year’s trip.

Vietnam Questions

The purpose of the medical mission was two-fold. One, to teach and train the resident and professors of the National ENT Hospital the techniques of facial plastic surgery. This was done in two ways. First, through hands-on teaching in the operating room. Both the residents and professors watched while the surgeons operated. In most instances, the American surgeons took the residents and or professors through the case and allowed them to operate, while the American surgeons watched and guided them.

In difficult cases, the residents and professors watched the American surgeons operate. In the afternoon, after the surgical cases were completed, the American surgeons lectured the entire department on various topics of facial plastic surgery, such as facial reconstruction after tumor resection, scar revision, and cleft lip and palate repair.

The second purpose of the mission was to operate and help those children and adults with complex facial deformities, facial tumors, or significant facial trauma.

The patients were selected throughout the year by the resident physicians as cases they believed were complex and difficult. By doing this, they not only selected patients to be helped, but also selected surgical procedures they believed they could learn from. On the Sunday right after our arrival, the team met and examined all the patients to make sure they were good candidates for surgery. It’s important to note that the residents did an amazing job selecting patients for the medical mission.

The team performed an average of five to six procedures a day. Usually every procedure was headed by one of the American surgeons with a resident or a professor assisting. In this way, the assistant was able to assist and take part in the surgery. The American surgeon took the resident or professor through the surgery so that they were able to get real, hands-on teaching of the complex procedures.

The trip began with a 20-plus hour, multi-stop flight. Dr. Bustillo’s flight, for example, began in Miami. From there he went to Chicago, Tokyo and finally to Hanoi. He left Friday morning Eastern Standard Time and arrived early Sunday morning Hanoi time.

On Sunday, the first day there, we went to the clinic in the National ENT Hospital and met all of the patients they had selected. The team then scheduled those patients for surgery throughout the week, taking into account which surgeon was best-suited for each particular procedure. The team spent a total of six days providing patient care. From Monday to Friday, the team operated from 8 a.m. to 4 or 5 p.m., and then gave lectures for several hours afterward.

A surgeon who is interested in doing missionary work should start looking at the various organizations that help to organize these missions. Our mission to Vietnam was initially organized by the International Face to Face program, which works under the American Academy of Facial Plastic Surgery. The Face to Face organization organizes many of these trips throughout the year, each going to different parts of the world. This particular mission was started approximately 20 years ago, and through the years has been led by different individuals.

Once I arrived in Vietnam, which is a 20-plus hour trip, the mission began. The very next day we were seeing patients in the clinic, examining them and making sure they were good candidates for the proposed surgery. At about 4 to 5 in the afternoon, you start to get extremely tired as the jet lag sets in. They say that it takes about one day for every hour difference to get accustomed to the new time, so this drags on for the entire trip. That afternoon, we lectured the residents for a couple of hours and then returned to the hotel.

Day two is our first surgical day. Things are done rather differently in Vietnam than in the states. For example, in some of the operating rooms, there are two surgeries taking place. Otherwise, the operating rooms are well-equipped and well-stocked with modern equipment and instruments. Most of the residents are eager to learn and help in any way they can. We operate throughout the day and then lecture in the afternoon. After the day is done, one of the professors will usually invite us out for dinner either to their home or to a restaurant. On a couple of occasions, my wife and I took the night off and explored Hanoi.

The entire mission is self-funded, meaning that the doctors pay for their airfare and hotel themselves. The airfare can be quite expensive, but the stay in the Hanoi hotel as well as the cost of food is very reasonable. This, of course, does not take into account the lost revenue from not working that week and continuing to pay office expenses. All in all it is an expensive trip, but well worth it.

This is a great way for medical students to learn medicine and help those in need. In the past, our mission has not had medical students, but we are definitely open to it and encourage it. Medical students should look for a mission that involves the scope of practice in which they are interested. For example, if a medical student is interested in facial plastic surgery, they may contact the American Academy of Facial Plastic Surgery and speak to someone associated with the face to face program.

There are many missions civilians can volunteer with. However, because this particular one takes place in a well-staffed hospital, there is not much need for them. Civilians who are interested in doing missionary work should contact the face to face program and inquire.

Each physician in the group took their own surgical instruments and sutures. We took our personal instruments because we are accustomed to using our own sets for the surgeries we perform. As a surgeon, especially in the field of facial plastic surgery, we get very comfortable with doing a particular procedure with a certain instrument. We took sutures because, again, we become accustomed to performing a particular procedure with a certain needle and suture.

The mission was organized by the face to face organization, a branch of the American Academy of Facial Plastic Surgery. This particular mission was started about 20 years ago and has changed hands various times. It was started by a mentor of mine many years ago, and currently is managed by the four of us who participate every year. Any physician or medical student interested should contact us.